Poverty leads to depopulation, not wealth - We already live in a dystopia

What if the actual reason for population decline are good old fashioned environmental constraints? Demographic crisis as a starting point for a wider assessment of the state of our societies

In animal kingdom, population is regulated by environmental conditions, such as availability of food and suitable living space, the presence of predators and their number, etc. If the living conditions in a certain environment are favorable for certain species, their numbers tend to increase until they reach certain limit. Either they will encounter a shortage of food, or adequate space, or predators will keep their numbers in check. Most of the time populations are stable, as factors leading to population increase are in equilibrium with factors leading to population decrease.

Sometimes populations can grow slowly for a long time, if they don’t encounter some environmental limits. And sometimes improvements in environment can lead to demographic explosions.

But population declines never occur if the conditions in environment are favorable for certain species to thrive. Population decline is always a consequence of some kind of adversity, either shortage of something like food, or increased number of predators, or some other environmental stressors, like the change in temperature or climate, etc. It never happens if conditions in the environment are favorable for the species in question to thrive.

(For nitpickers: maybe you can find some rare exceptions, but they don’t invalidate this general rule)

So if we assume that general principles of population dynamics are the same for human population as for animal populations, then we can arrive at the conclusion that the demographic crises and possible population decline that’s projected to start on the world level in the second half of 21st century, and which has already started in many parts of the world has the same causes as any population decline event in nature, namely certain environmental restraints, shortage of something, or generally unfavorable environmental conditions.

Now this seems to be in a sharp contrast with the observed trend that wealthiest countries and countries with highest welfare indicators such as human development index have the lowest total fertility rates. Everyone knows that GDP per capita and total fertility rate are inversely correlated. So it seems that I should throw my hypothesis out of window? After all, it seems hard to argue that the environmental conditions in developed countries with sub-replacement fertility are poor or unfavorable for humans. We have plenty of food, so much that we throw away a large part of it, most of us have homes, clothes, medicines, plenty of opportunities for entertainment and enjoyment of life. Perfect conditions for human species to thrive?

Not so fast!

I’m going to argue that people in developed countries are actually poor in some very important domains / senses / aspects, and that this poverty (and not the aforementioned material wealth) is the environmental constraint that leads to sub-replacement fertility and population decline.

We might be rich in money, gadgets and food, but here are some very important things in which we are poor:

Time poverty

We are time poor in two important senses: on a lifetime level - a huge chunk of our most fertile years are taken up by education and early careers when we’re struggling to stand on our own foot and finally launch; on an everyday level - we spend long hours each day working, preparing for work, commuting to work, that there doesn’t remain much time for other activities. Each of these types of time poverty merit some further discussion.

Time poverty on macro (or lifetime) level

Civilization shifts humans away from their natural condition to some degree. But you can only go so far away from the demands of nature and biology before you run into problems. Most of our natural needs are still met, even now in 21st century, in the old fashioned ways: we eat when we’re hungry, we drink when we’re thirsty, we sleep when we’re sleepy (and in spite of all the modern distractions we typically do manage to get at least 7 hours of sleep).

But there is one important exception that has to do with our sexual and reproductive function: we don’t start having kids when we’re supposed to. This is a big deal. This shouldn’t be understated. This is an unprecedented situation!

For the most of the human history we used to start having kids as early as we were able to or shortly afterwards - that is as soon as the puberty ends and we reach sexual maturity. This is normal. This is how it’s naturally supposed to be. And this is the case in almost all other animal species. When you become sexually mature, you start reproducing. Delaying it for a few years (like till early 20s) is not a big deal and was often the case in history. But now we’re delaying it for decades, and this is a big deal.

Education and early career struggles, attempts to establish ourselves as full adults, often takes our entire 20s. More than half of our most fertile years are taken up by education and struggles in early career. Sometimes education itself is prolonged for way too long.

We’re time poor in sense that we often only get to use the last third of our best reproductive years (or in case of women - of their entire fertile period) for actual reproduction. Two thirds of that precious time period is in some way stolen from us. We marry way too late, and then we simply don’t have enough time to have as many kids as we would want to have.

Time poverty on micro (or everyday) level

On everyday level time poverty means that we have way too little time for ourselves, and also very little time for our kids.

First of all, eight hour workday might look great if we compare it with conditions of factory workers during early industrial revolution, when they sometimes worked up to 16 hours a day. But if we compare it with conditions during most of human history, we can conclude that we work way more than we did in the past.

Here’s an article showing that people in middle ages worked way less than we do today: Pre-industrial workers had a shorter workweek than today's

(Now there are some opposing views that are trying to debunk it, but they might be motivated by 1 - attempt to defend current system and 2 - attempt to discourage romanticization of the past. Some criticism might have some merit, but the thesis itself has some merit too and is not really debunked)

Second, it’s not just about how much we work, but also when we work, and who works.

Nine to five workday - which can easily become 8 to 6 when we include getting ready, commute and occasional overtime - is particularly unfavorable towards parenthood, family, and raising kids. We only get evenings for ourselves. And evenings are not the time when we’re at our best or freshest or whatever. Our energy levels are low, our nerves are exhausted, and the quality of time we spend with our kids isn’t likely to be too high.

Regarding the question “who works” - the answer is - all adults, and this is another unprecedented situation.

Never before in history did women work full time away from home. While we should celebrate the fact that women can get all the jobs that men get, and be equal in everything, and pursue their dreams in all domains, including career, we shouldn’t be so happy about the fact that today it’s not just an option that’s available to women, but also a strong social expectation, and practically an obligation.

Also, celebrating gender equality, should not prevent us from trying to assess the effects of such social expectations on families, fertility, and on women themselves.

Equal opportunity, having equal options, having free choice to decide what their best life is should never be questioned, and should always be celebrated. This is one of the great victories of feminism that should be respected and cherished.

But imposition of demanding new social expectations can and should be questioned and criticized and we should feel free to assess the effects of such expectations.

And here are some of the effects:

The fact that mothers work full time, means that raising children becomes more expensive, because paying kindergarten or nanny becomes obligatory.

Mothers spend less time with their kids, and they especially spend less quality time, as in the evenings they are often quite tired or, as the next point shows - busy:

Since we still haven’t completely abolished traditional division of labor at home, women are typically overworked in today’s system. Not only do they work 8 hours at work, they also get to work the lion’s share of domestic chores such as childcare, cooking, cleaning, etc.

This makes many women stressed, unhappy and dissatisfied in marriage, which leads to an increased rate of divorces, often initiated by women.

Shelter poverty

Probably, I don’t even have to tell you that housing prices have been skyrocketing for a long while already. According to some often cited statistics (that I didn’t verify, but which sounds very plausible to me nevertheless) in the 1970 a typical house cost about 1.72 times average annual (single income) salary in the US. In 2022 it cost 7 times the average annual income. Similar trends are present in other countries as well.

According to this article average couples would buy a house in the UK at the age of 26 in 1974, while in 2024 this shifted to 33 years and 8 months.

I will not go in much detail about these statistics, you can find a lot of that stuff on your own. Instead I’ll try to look at the causes and what it means for fertility.

Three main causes are as follows:

More people, increased demand, limited supply - simply, there are more people today and the amount of space is the same. Especially in the cities or suburbs that are close enough to big urban centers the amount of space is limited, and the number of people has risen, not just due to natural increase, but also due to migrations from the countryside towards urban and suburban areas. This increased demand for real estate drives prices higher. At the same time prices of property in rural areas typically didn’t rise as much, but many people simply don’t want to live there.

However, due to increased unaffordability of the housing in urban and suburban areas, it seems that many people have been forced to choose to live in rural areas, and now even there, the prices have started to increase and outpace the rise of (already astronomically high) prices of property in urban areas.

Smaller households - Even today, when in many developed countries population is stagnating or even started declining, the number of households is still rising. And the demand for housing depends on the number of households, not number of people. People prefer living in smaller nuclear families or on their own. Big, multi-generational households are becoming rare. This leads to further increase in demand for housing, and drives the prices up.

Homes as investment - houses and apartments are more and more often treated as investment especially by large-scale corporate landlords and real estate investment trusts (REITs) and other institutional players. This further increases not just the prices of properties but also rents, making housing increasingly unaffordable for young couples.

One of the reasons for such institutional demand for real estate as investment, is the expansionary monetary policy and low interest rates. This increases money supply and creates inflation, and that extra money often ends up invested in real estate, stocks and other asset classes, creating series of economic bubbles, and inflating prices of everything.

But this doesn’t mean that the tight monetary policy would be a solution, as it comes with its own problems - loans would be more expensive, interest rates higher, and the construction sector would be negatively affected, eventually bringing less housing on the market, creating decrease of demand, which can, again, lead to increased costs.

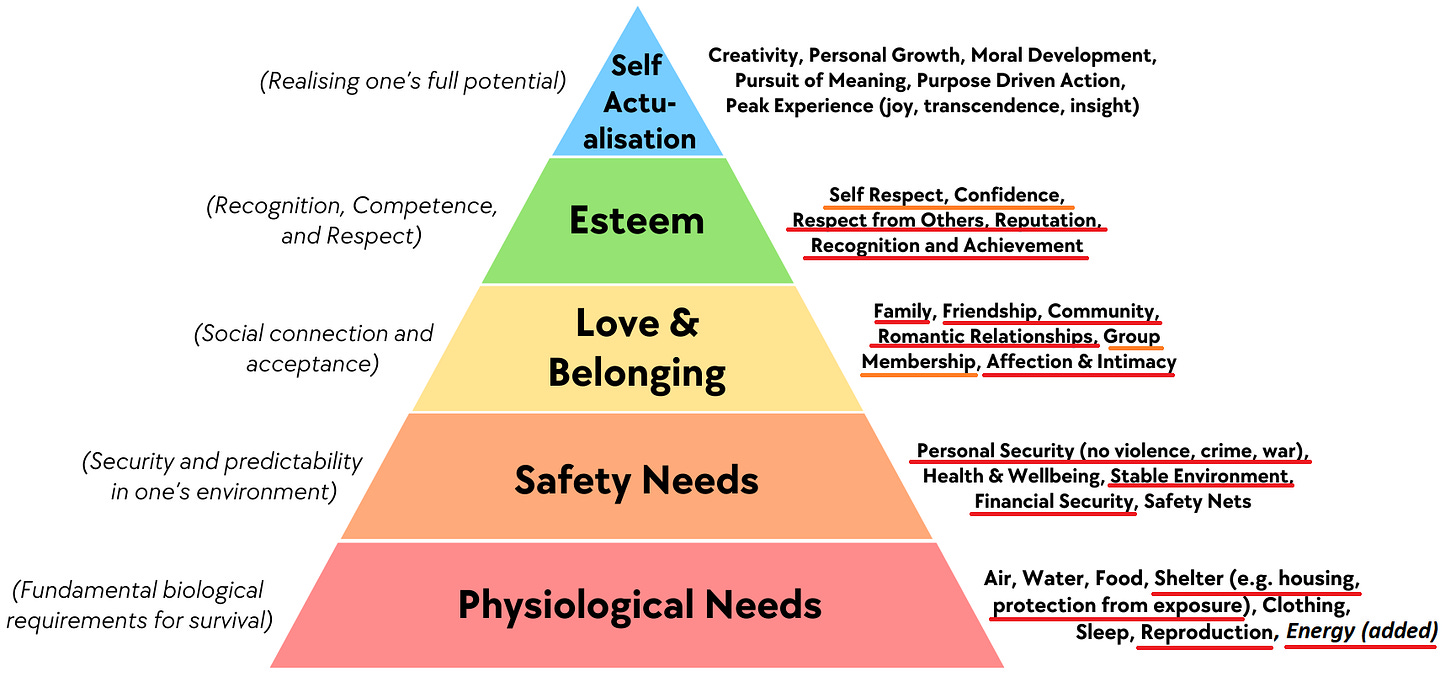

The actual solution is much more complex and goes beyond simplistic monetary policy choices. I’ll talk about it a bit more later when I focus on solutions. For now it’s important to bring home the fact that housing is increasingly expensive and unaffordable to many young people, so talking about actual poverty of shelter in our modern developed societies makes a lot of sense. Don’t forget that shelter is one of the most basic and fundamental human needs according to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. It’s at the very foundation of hierarchy of needs.

Status poverty

It’s a bit stupid to talk about status poverty on a whole population basis, because status is always relative to other people. Status is a zero sum game, and the total amount of status in the whole world is constant.

However, it is very important who has status in society and how hard it is to obtain status.

If you need status in order to be a desirable dating partner, and such status is hard to obtain, and is usually held by older people, who are nearing the end of their fertile years, this situation is very unfavorable for fertility.

This is tightly related to time poverty, especially on macro (lifetime) level. We are spending most of our 20s on things unrelated to parenting and reproduction, not out of our whims, but out of need. We’re doing all these things - completing education, establishing ourselves in careers, stabilizing our finances, etc… in order to increase our status - and such status is necessary for dating success.

Societies in which status is hard to obtain and in which it takes a lot of time to obtain it and is held by older people and yet required for dating success are actively hostile to fertility and reproduction.

And don’t get me wrong. This is not only case among the men. Increasingly, there are higher and higher social expectations for women as well to have some status, education, careers, etc, in order to be desirable partners. Such demands are not as strong as in men, and can be compensated by physical attractiveness, but they still do exist, and for this reason even large majority of women spend a better part of their 20s on status obtaining activities - or should I say - trying to escape status poverty, which typically uses up to half of their entire fertile period.

For the most of the history, people typically achieved their full status much earlier in life, typically, as soon as they became adults, that is by the age of 20. There was less social mobility, less chasing of status, education lasted shorter (if at all), and people’s status depended either on the class their were born in (their origin), or on the objective characteristics they couldn’t influence much, such as having good genetics and being attractive. But in any way, what status you managed to achieve by the age of 20, that was it. So at that age people would typically marry with other people of comparable status.

Nowadays, almost everyone is poor when it comes to status at the age of 20 and needs to chase it for a long time before they can become a good “marriage material”.

And just for the record, status is also in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, though it’s on the second to last floor, just below self-actualization.

Energy poverty

Energy poverty is closely related to other types of poverty discussed earlier, especially time poverty and both on everyday level, and on lifetime level.

On an everyday level when they return home from work, parents are objectively tired. Modern jobs typically involve contacts with multiple people, constant demands for availability, a lot of emails, dynamic environments, and even when they aren’t too demanding physically or cognitively, they often assert significant psychological pressure. There are always some new projects, deadlines, changes, etc… Often people bring work home, and need to stay available on their work phones, even when they come back home. Working overtime isn’t rare either. All this leads to exhaustion - mental, physical and psychological. So parents don’t really have that much energy to dedicate to their kids - and the more kids they have, the harder it becomes. For many busy parents two kids is about the maximum they can “manage” without a serious burnout.

On a lifetime level - we accumulate psychological fatigue after all that status chasing in our 20s and early 30s. When the time arrives for raising kids, parents typically aren’t in their best psychological shape.

In fact some research seems to confirm it. It seems that our happiness follows a U shaped curve - displaying high values in childhood and adolescence, and again in senior years, and bottoming out in our 30s and 40s - years in which most people are most actively involved as parents.

So it affects not only the number of kids we are able to raise, but also the quality of relationship we have with them. Demands of work often compromise all other aspects of life, including parenting.

Poverty of stability

Stability and safety is another of basic human needs according to Maslow. And today it also seems to be compromised. People are scared (justifiably) of the future. Geopolitical situation is tense and we have the means to destroy much life on this planet; climate change concerns have become mainstream, and nowadays the concerns about technological advances are added to it and are increasingly seen as a potential existential threat, not just in small circles of rationalists and effective altruists. Doomerism is a thing and is more and more prevalent. And I repeat, it’s justified and it’s not irrational. We are indeed at crossroads. The next couple of years or decades could be incredibly influential in determining the future of humanity and civilization, for the better or the worse. People can hope for the good outcome, and work on it, by tackling some of the world’s most pressing problems , but right now there seems to be a little assurance of such good outcomes. The world we live in doesn’t seem stable, and our future seems quite uncertain and perilous. And this poverty of stability is another reason why many people don’t feel inclined to have kids.

Money poverty (or actual poverty)

Actual poverty doesn’t seem to be a big issue, at least not in developed countries. But we should question this as well. In absolute terms, we’re richer than ever, that’s for sure. But in relative terms, we might still be poor in some very important ways. Or at the very least we often feel this way.

Poverty relative to others

First, we can be poor relative to others - wealth and income inequality are skyrocketing and while they don’t have that much effect on living conditions (we still live very well in comparison to how we lived in the past), they do have effect on our status. Comparison leads to feelings of inadequacy, and differences in wealth lead to real and/or perceived differences in status.

You might say that in the past inequality was even bigger, as most of people were poor and low status, they were serfs / peasants for example. Yes, that’s true. But within this large group of people that comprised majority of population, differences weren’t that big. With the exception of tiny higher classes, everyone was poor, but everyone was equally poor. And that was normal and accepted. Everyone was low status, but everyone was equally low status. And when everyone is equally low status, it doesn’t matter. Status only matters in comparison.

Also, social mobility was practically non existent. People didn’t even dream about it. People were more or less happy (or at least at peace) with their status regardless of how high or low it was. And people didn’t spend much time fantasizing about higher classes or envying them, as they were distant, and they didn’t even have much contact with them.

Today, every day we see celebrities and billionaires on TV and social media, where they are championing their luxurious lifestyles. And we are sold the idea that social mobility is possible and that everyone can reach for the stars if they just try hard enough. Social mobility is possible, no doubt about it, but it’s hard, and most of the people don’t succeed in that pursuit, but the idea itself, chasing such status, can have many detrimental psychological effects, and can make people feel inadequate.

People don’t chase higher status out of some sick ambition, or because they envy the rich, or because that’s some whim or caprice of theirs… people chase higher status out of necessity, as there are real penalties for failing to reach, and once reached, for failing to maintain certain levels of status.

One of such penalties can be divorce. It’s not uncommon, especially for men, to face the possibility of divorce if their status falls below certain threshold. Typically they are expected to have at least the same status as their wives, and if they fall below that level, the chance for divorce rises significantly.

As we now live in the world in which social mobility is officially possible, maintaining one’s status requires constant effort and work. We don’t work just to earn enough money for what we need, but we also work to earn enough money that would keep our status above certain thresholds.

So we live in the world of constant competition, Moloch dynamics, and keeping up with the Joneses. It is not just about if you have enough money for yourself and your family, but it is about if you have enough money to win at the status game.

Wining at such a game requires a strong focus on career, which leaves little time for family, parenting and anything else.

Poverty relative to self-imposed standards and social norms

This is closely related to what we already discussed, but there is a slight difference. When status is our motivation, we chase money explicitly in order to compete with others. When self imposed norms or social norms are our motivation, we chase money because we truly believe in certain standards of living that are required in order for us to be good parents, and it doesn’t need to be necessarily competitive. We might honestly believe that our kid needs the best kindergarten, summer and winter vacations and multiple extracurricular activities in order to properly develop and to grow in an environment that is enriching enough. There might be a grain of truth to this belief. After all - more stimulating environments are indeed better for development. But we often take it too far. Many of very successful people in the past grew into great writers, diplomats, scientists or artists even if they grew up in much poorer environment, without all those things that parents are now trying hard to ensure their kids have.

So, yes, we are wealthier than ever in history, but we live in a very competitive world and position of each person relative to others is what matters, and there’s no level of prosperity that could solve this problem. Even if everyone all of a sudden started making 10 times more money, those differences between people and race dynamics would persist. So the only way to solve this problem would be to transform our societies in such a way that they become more egalitarian and less competitive. Or alternatively, if there’s no way to overcome inequality, perhaps we would be less miserable if we found ways to be happy with our position, instead of always chasing higher status.

We are already living in a dystopia

To sum up what I discussed so far:

I’ve shown that the reasons for demographic crisis are not to be found in the fact that we’re wealthier and more developed - it’s the opposite, the real reasons are the constraints of the environment, adversarial, unfavorable conditions in our society, unfavorable to human thriving, unfavorable at least for one of the basic functions of every species which is reproduction.

These constraints are manifested in various forms of poverty that I discussed: poverty of time, shelter, energy, status, stability and eventually even monetary poverty, at least in comparison to others (due to competition), and in comparison to our self imposed or socially imposed standards.

Sub-replacement fertility is not normal. It’s a symptom of unfavorable conditions in the environment or of dysfunctional or pathological society. We live in a sick society. It shouldn’t be a problem to say it loud.

A society that is fine and functional can’t have a fertility rate that’s well below replacement level. Something (or many things) about our modern society is deeply wrong.

This post is not future oriented. Today we live in an extremely unstable and uncertain world where it’s very hard to predict the future. Black swan events have stopped being surprising. I’m not worried about existential risk due to population decline… not because this issue itself is unimportant, but because we’re facing way more urgent existential risks and threats. But with this post, I want to show certain present pathologies of our society and to see if there are any possible solutions. Luckily, I think there are some solutions, and perhaps the problem will resolve itself on its own. But before discussing solutions, let’s underline once more the fact that we’re living in a dystopia. I’ve said already that in our modern societies, we’re poor in some important ways, which prevent us from fulfilling some of the most basic human needs, according to Maslow’s hierarchy.

The following pictures shows Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. I’ve underlined all those needs that are seriously compromised and often unmet in modern societies:

Besides those needs directly related to reproduction that I already mentioned, we’re often lacking in some other needs as well, such as:

family - divorce rates are high, children often don’t live in stable families - and this too, could be caused by chasing status, career, etc… and due to instability of our hard earned status

friendship - loneliness seems to be an epidemic and people are spending less and less time with their friends. Friendship recession is a thing, and it already has a Wikipedia article. We have less friends, and we spend less time with those friends we (still) have. And this too, could be due to relentless pursuit of money and status and ambition. (Though technology is another really big factor)

romantic relationships, affection and intimacy - Many studies show that more and more people are single, at all ages

community - third places have less and less prominent role in society, people are increasingly distant from their neighbors and their local communities…

So it’s not just that our needs related to reproduction are unmet - many other important needs seem to be chronically frustrated in our modern societies. And in such a situation, it’s only normal that it will eventually be manifested in some negative way, such as with sub-replacement fertility.

Natural environmental constraints or self-imposed environmental constraints and dysfunctions?

It’s worth wondering if our situation is caused by natural constraints of the Earth ecosystem, or they are in a way self-made and self-imposed.

The fact that human population exploded in last 200 years shouldn’t be ignored. Now there are way more people in the world than in any other historic period. Current population levels are unprecedented.

It seems that we’re likely to completely exhaust some important natural resources.

Maybe we’re nearing the Earth’s carrying capacity, perhaps Earth simply can’t provide enough resources for many more people than there already are on the Earth.

In 1972 a group of scientists commissioned by the Club of Rome, wrote an infamous book The Limits to Growth, which highlighted the possibility of societal collapse and swift population decline sometime in 21st century, mainly due to resource depletion.

However, various Malthusian arguments like this one, have routinely been debunked in history. But still, we should be aware of the fact that our current population level is unprecedented and that we’re exhausting Earth’s resources faster than ever.

Now, I’m not sure if it’s possible for a complex system such as Earth, to indirectly, in some complex ways, influence human society in such a way to cause population decline. I’m not sure if it’s possible for the limits of resources and Earth’s carrying capacity, to somehow manifest via observed constraints - the types of poverty that I discussed so far. Perhaps there is some complex mechanism for this, which isn’t very clear to me.

One way the Earth could “send signals” to human society is through prices. When resources are limited and rare, they become pricey. And some things stay expensive and not easily available, in spite of our enormous increases in technology and productivity. Perhaps housing is the best example, as land at attractive locations is indeed a limited resource that many people are competing for.

But, more generally, I think that the current demographic crisis that we’re facing is not caused by natural limitations of Earth and its carrying capacity. This too would occur eventually, if population kept increasing indefinitely, but I think we’re likely to avoid this scenario.

Still, demographic crisis and population decline are indeed caused by environmental constraints, that is certain types of poverty and unfavorable conditions for human thriving, but, I think they are mostly self-imposed and self-caused. They are mostly due to dysfunctions and pathologies of our modern societies, and less due to us reaching the limits of Earth’s carrying capacity.

But regardless of the cause, whether we are facing Earth’s limits or our own social limitations and dysfunctions, one thing is clear: our current way of life is unsustainable and dysfunctional. In a way we’re too high maintenance as a society, our societies are perhaps too complex and too demanding for an average person.

Here’s what DeepSeek told me when I asked it when it expects developed countries to reach replacement fertility once again:

Short-to-Medium Term (Next 20-30 years): It is extremely unlikely that the majority of developed countries will reach a sustained TFR of 2.1. Some countries with robust policies might get closer (e.g., 1.8-1.9), but 2.1 remains a significant hurdle.

Long Term (Beyond 50 years): While prediction is very difficult, current trends and the entrenched nature of the drivers suggest that a widespread return to sustained replacement-level fertility in developed countries is improbable without unforeseeable, revolutionary societal, economic, or technological transformations. Sub-replacement fertility seems to be a persistent feature of advanced development.

Therefore, the most probable answer is that developed countries will not reach a sustained TFR of 2.1 again in the foreseeable future (likely not within this century under current trajectories). The focus for policymakers is shifting towards adapting to aging populations and persistently low birth rates rather than expecting a return to replacement level.

The most ominous sentence in its reply is this: Sub-replacement fertility seems to be a persistent feature of advanced development.

So either we make some fundamental changes to our societies or we’ll be stuck with sub-replacement fertility forever (that is, until we die out, unless something kills us before that). I’m not worried about that - it’s a very distant future threat; but I’m worried about our trajectory and about what this says about our current society. Sub-replacement fertility, IMO, is a symptom of our current social pathology and dysfunction. It’s just one of the ways to know that we’re living in a dystopia.

Brainstorming potential solutions

The solutions I’m proposing are straightforward and derive directly from problems themselves, but these solutions are not “cosmetic” and they can’t be easily implemented through standard pro-natalist policies. They require fundamental changes of some important characteristics of our societies. Here I’ll list proposed solutions for each of the problems that we discussed:

Time poverty on macro (lifetime) level

Perhaps, we could take advantage of new technologies to accelerate education process. AI tutoring could allow personalized education for each student. They would still physically go to school and socialize with other students, but each student would have a different, optimized, self-paced trajectory. The teachers would follow each student personally and would try to make sure they are on the right track. The point of this whole thing would be that everyone can finish their entire formal education by the age of 18 to 20. This is the age by which we should be full and complete adults, and completely ready to enter the workforce (that is, unless AI takes all of our jobs).

Optimized and personalized curriculum would mean that gifted students might reach PhD levels of education by the time they are 20, bright students might reach master level, average students could reach college level, those below average could reach perhaps high school level - but they would all finish their entire education roughly at the same time.

That would free up a big chunk of time in their 20s to be used for what it is biologically supposed to be used - reproduction.

Alternatively, if speeding up education doesn’t work, perhaps we should require college education only for those jobs where it is really needed. Today majority of white collar jobs require college education, even though it is not really needed for accomplishing daily tasks at work.

According to some theories, college is more about signaling than anything else. The point of getting a degree is to prove that you’re smart enough and conscientious and responsible enough to be a good worker. Or, additionally, in countries with expensive education, to prove that you’re serious enough about your career ambitions, that you’re willing to invest a significant amount of money in that pursuit. And having to pay back student loans is another guarantee to an employer that you’ll keep working, and not decide one day, all of a sudden to quit.

Signaling works and it has a legitimate function - but the thing is - there are better methods to assess all those things about potential workers, in ways that won’t waste them a couple of most precious years of their youth.

If interested in intelligence level of workers employers could include an IQ test in recruiting process. If interested in how responsible and conscientious they are, they could give them some hard-to-fake personality test.

Yes that would be more expensive for employers and would require them to do more work, but that would eliminate the need for such expensive signaling. Wasting 4 years on education that you don’t really need is highly costly on a societal level.

Perhaps we could establish trusted institutions for IQ and personality testing, that would issue IQ and personality certificates, so that we can remove the burden of testing from employers.

That would, unfortunately be very bad for those people who are not intelligent enough or who have problematic personality, so we would need to take care of them in some ways as well, perhaps via UBI (Universal Basic Income), or in some other ways.

We could also perhaps research and try to develop methods for increasing IQ and improving personality.

I am not actually endorsing any of those “solutions”, and I’m aware that they sound quite dystopian, but if we don’t solve the problem in some real, meaningful way, it will keep existing indefinitely. I’m just exploring the space of possibilities, and the main point of this is to show just how big changes, that are quite outside Overton window, would be needed to significantly influence demographic trends.

We as a species simply aren’t meant to start reproducing in our 30s, and to spend most of our 20s just preparing for real adult life. So in order to return to a life that would be more in harmony with our nature, we would need to make some quite big changes to our way of life.

One of the ways in which this situation could resolve itself on its own is if AI and automation frees most humans from needing to work, and therefore also from needing to gain skills related to work. But this doesn’t guarantee that we’ll start launching our adult lives earlier. Education could be transformed from something you need to do the work, to a goal in itself, and a status symbol. And this could maintain the trend of spending most of our 20s in education, as we chase certain status. So I guess accelerating education would be favorable to fertility in all cases, and the real question is whether such a proposal is acceptable to us or not.

Time poverty on micro (everyday) level

Regarding time poverty on everyday level, we should simply recognize that we don’t have enough time for ourselves and that we’re overworked, especially women, since they do most of the housework on top of their regular jobs.

There all the things that improve position and lives of workers could be a part of the solution. This includes the following:

Supporting pro-labor politics. Supporting worker unions. Supporting minimal wages.

Advocating for shorter workday - 6 or 7 hours as opposed to 8.

Considering shifting workday to earlier hours. Instead of starting at 9 AM, we could shift it to 8 AM or even 7 AM. That would allow people to have more of the daylight time to themselves and their families. It’s not normal to have only evenings for yourself.

Considering shorter work weeks as well. Some experiments have showed that with 4 day work week, productivity can increase and total weekly output can stay the same or even slightly increase.

Increasing the duration of parental leave.

One very important measure would also be trying to force companies to guarantee to women easy continuation of their careers even after a long parental leave. If women are assured that their career will not suffer due to parenting, they will be much more likely to decide to have kids. For this reason their job positions must be secure, but not only in sense of not losing jobs, but also in sense of being able to advance in their careers with no slowdown (except for the time they were actually absent). The point is, the companies should not consider women less important workers due to their parental absences. There shouldn’t be any kind of implicit discouraging of having kids by the employees.

De-stigmatizing the choice of one of the spouses to work part time, or not to be employed at all. Right now, not being employed or working part time is stigmatized. We make jokes about stay at home dads, and even if the wife is the one who chooses not to work or to work part time, it’s still stigmatized to to some extent. We have that idea that everyone should have their dream career and work away from home. I fully support that everyone has each and every opportunity to pursue any career that they wish, but I think we should not judge people if they choose to be homemakers. For some people that would make their life less stressful, more fulfilling and allow them to dedicate more of their time and energy to raising kids.

Modifying labor division at home. If both spouses work full time and dedicate the same hours to work that brings money, then they should also equally contribute to household chores. This unfortunately often isn’t the case. Typically women work more at home, even though they have equally demanding jobs. This over time can lead to accumulating frustration, dissatisfaction, burnout, etc… and it can be one of the reasons for divorce. It’s no wonder why women initiate most of divorces. If we’re honest about it, in today’s system, marriage is much better deal for men, then for women. So by freeing the women of some of the burden of household chores, many marriages could be saved from divorce, and a saved marriage would likely result in more kids over time.

Now, this whole discussion so far assumes business as usual scenario. But such scenario is increasingly unlikely with the advances in AI and automation. In a couple of years we might be dealing with massive unemployment due to AI. This could potentially solve this whole problem on its own, freeing people from work and allowing everyone to enjoy prosperity. But there’s no guarantee of such an outcome. I think we should start thinking already about post-labor economics and how to ensure prosperity of people if they can’t earn money from their work. Universal Basic Income or some other system would be indispensable in that situation, to ensure livelihood of huge numbers of people.

But before this happens, implementing some of these “business as usual” solutions wouldn’t hurt, and it could also be a good starting point for establishing this new post-labor economy on healthy foundation.

Shelter (housing) poverty

Prices of housing are definitely too high, making homes less available to young couples, and often delaying the time they can buy a house or apartment. So we should definitely be working on lowering those prices and making housing more available. At least we know what we should do, the question is how.

We saw that monetary policy is a rather blunt instrument for managing housing prices. Both too lose, and too tight monetary policy would likely have some drawbacks. Since current practice is closer to the “too loose” side of the things, causing bubbles of all sorts of assets, just a tiny bit tighter approach to monetary policy might be worthy of consideration.

But the real solution for high housing prices is outside of monetary policy. Here are some things (among many others) that could help with this:

Changing zoning laws and regulations to allow taller buildings and higher densities. This could lower the costs of apartments by reducing their land footprint.

Speeding up the process of getting building permits. Reducing such time from 2 years to 1 year, could cut the final property prices by 10-20%.

Social housing - governments could build large housing projects and sell them at below market prices to qualifying buyers - like young couples.

Taxing empty homes - governments could tax more severely those housing units that are unoccupied most the year. That would discourage speculation (buying homes just as an investment), and it would also encourage existing investors to rent those houses, thus increasing the supply of homes available for renting and lowering the rents.

Taxing unused land - the land tax for unused land should be higher, to encourage owners to build on it and provide the market with more homes.

Higher taxes for homes that are sold soon after buying, to discourage flipping and speculation.

Subsidizing construction industry to increase the number of companies in that sector, to increase the competition, and lower prices of construction.

Tighter mortgage lending rules for investors. - If someone is buying a housing unit with no intention to live there, government should require banks to follow tighter rules in that case before approving the loans. They should require higher down payments and offer lower loan-to-value rations in those cases.

Status poverty

Status poverty is when young people in their best fertile years can’t easily obtain status needed for reproductive success - it takes a lot of time and energy. Also status is usually held by older people.

The things that I mentioned for reducing macro-level time poverty, would also be helpful here: accelerating education, requiring college degrees only when they are truly needed for a job, and the most controversial of all - issuing IQ and personality certificates to eliminate the need for signaling, and to make education really about education - these things could allow young people to obtain status quicker and therefore it would reduce status poverty in young, fertile people.

Also all the measures that would help decrease economic inequality generally, such as progressive taxes, welfare, public health and education, and generally left-leaning policies - but in sense of true social democratic left, things that tend to decrease Gini index, they would also likely help decrease the perceived status poverty in young people. In more economically equal societies, material wealth isn’t the most important thing as most people have a decent standard of living. Therefore, such conditions should be expected to decrease the status race.

Or maybe the status race would persist, but it would be based on things that don’t take decades to accumulate, such as wealth, career success, etc… but on things that can be obtained much faster, or are even inborn, such as attractiveness, personality, interests, hobbies, knowledge of popular culture etc.

Energy poverty

The things that would reduce time poverty on everyday (micro) level, would also reduce energy poverty. If we’re less overworked, if we have more free time, we’ll also be less tired and have more energy, so there’s no need to add anything more here.

Poverty of stability

Poverty of stability can be solved in two ways. Either we as a civilization become more robust, and decrease our existential risks, such as risks of AI, climate change, large power conflict, etc… or we change our attitude towards these risks.

Of course, lowering those risks is of the utmost importance, and this is probably the most important problem right now in the world. But even while we’re still facing risks, our attitude to those risks matters.

A common way of thinking is “I don’t want to bring kids in such a crazy world.”

I fully understand this way of thinking. When we’re living at the precipice of history, in one of the most risky periods ever, and it really makes sense to question the sanity of bringing kids in such a world, who could, if things go wrong, be the last generation to be born on this planet.

But, if we allow ourselves to be dominated by such a logic, this means, on some level, that we have already given up. This means that we don’t believe in the future.

I think this attitude is not good, and might be even harmful when it comes to existential risks.

Why? Because when you do have kids, you’re also way more motivated to give those kids the best possible future. So people with kids will also be way more motivated to do all in their power to help, any way they can, in lowering those existential risks.

On the other hand if you don’t have kids, you might care less about the future and about what happens after you die.

Money poverty (relative to others)

This is all about chasing higher status and competition. There are 3 possible solutions:

creating a truly more equal society in which such competition wouldn’t make as much sense as it does today and status wouldn’t be so closely tied with material success. Instead it would derive from more intrinsic characteristics of a person which can be visible much earlier. (So we’d have most of our status at the age of 20, instead of 35 or 40)

debunking the myth of social mobility, which would lead people to look at their status with more acceptance. Social mobility is not really a myth, it’s definitely possible, but it’s much harder than people realize - to the point that popular conceptions of social mobility do look quite like a myth. (But this second option is already bordering dystopian)

stabilizing inequalities - that would be by far the worst and most dystopian solution, but it could be a solution nevertheless. In societies in which inequalities and class differences are stable, people aren’t even considering social mobility, and instead accept their status as given. That would remove some of the competition and it would free up our time in 20s, so that we can dedicate it to other things instead of this status race, but it would lead to a society with deeply entrenched inequalities, which would be a step in the wrong direction for civilization. I can’t accept this as a desirable solution.

Money poverty (relative to self-imposed or social standards, norms and expectations)

This type of poverty, is luckily, somewhat easier to solve.

We need status to attract partners and to get into relationships that we desire. But this second type of poverty relative to certain self-imposed standards usually becomes relevant when we’re already in a relationship and have kids. And for this reason it might be somewhat easier to disregard some social norms and self-imposed standards. Perhaps popular psychology, influencers, self-help books, etc… could make a positive influence if they start changing their dominant narrative from: “You must do all those expensive things in order to be a decent parent”, to “good parenting is about caring about your kids, showing them love and understanding, and not about how many vacations, gadgets and extracurricular activities you provide them with”.

Until such ways of thinking become more prevalent it is up to each person to try to emancipate themselves from certain social norms about parenting that make very little sense from the actual psychological and developmental point of view.

We should doubt all those high standards, because sometimes they serve just the interest of capitalism and make profit for all those companies that provide all those expensive products and services, instead of serving the real needs of kids.

I could bet that an extra hour of quality time that parents spend with their kids, is much more valuable than an extra hour of extracurricular activities.

We also forget that extracurricular activities are not only expensive, but they are all structured, and this eats up the free time that kids have and that they should probably use for socializing with their friends, siblings, etc.

Could we really endorse ANY of those solutions?

Some of the solutions I recommended here are somewhat controversial. Let’s take a quick look at their potential effectiveness in increasing TFR, whether they are in Overton window, and whether I would personally endorse them.

What comes to surprise to me after making this table, is that many of the proposed solutions aren’t that controversial after all, and I could endorse most of them with some notable exceptions - IQ and personality certificates, and stabilizing inequalities.

Would those solutions really solve the problem in long term?

First of all, it’s highly questionable whether implementing those solutions would gain any public support and whether anyone would be willing to implement them. Second, even if implemented, there’s no guarantee that they would work.

But, assuming that they do work, and we get total fertility ratio meaningfully above 2.1 in most of the countries, would this solve demographic problems forever?

I guess not, because unless we start spreading to other planets, population growth will eventually need to stop, and the population will have to stabilize at some level. It simply can’t keep growing forever.

But, right now, we have much more reasons to worry about population collapse rather than about overpopulation.

Furthermore, when we arrive to the point where no more growth is possible or desirable and we need to stabilize the population, there is a big difference between population stabilization due to some voluntary, intentional social consensus about how many kids it’s desirable to have (for example we could make a strong social norm to have around 2 kids, or 3 at most, and not more than that number) - and our current situation in which we’re failing to reproduce in sufficient numbers not out of our own volition, but due to various limitations that our social and economic landscape is imposing onto us effectively preventing us from reproducing. Right now it’s not that we don’t want to reproduce enough (although some might think so - but they should ask themselves WHY, what is causing people not to want kids), it is that we can’t due to many types of poverty which I discussed so far. Or in other words we can’t due to dystopian conditions in our society that we don’t recognize as dystopian because they are the only conditions we have ever lived in - so we normalize them.

Why does this whole discussion matter at all?

I’m not worried about human extinction due to population decline. There are other things that can kill us much quicker. So this whole post is not so much about distant future. In the distant future, in business-as-usual scenario (that is without some major disruption or catastrophe), the demographic crises might solve itself on its own. Eventually those who value having kids and large families will out-breed those who don’t, and the strong inclination towards having kids will become a new evolutionary trait that we’ll likely acquire.

But there are two important reasons:

Even if it doesn’t cause extinction, population decline will likely cause many big problems.

First of all, low fertility leads to aging of population. Population in which the number of retirees rivals or even tops the number of working people is bound to have huge economic problems. Relatively few workers would have to support a large number of retirees, putting additional stress on their work lives. This can only be avoided if automation frees most of us from the toil of work. If machines are capable of producing enough goods for all the workers and the retirees too, then this might solve itself on its own.

However, aged population is also likely to be less creative, generally less vibrant, less energetic, less innovative, etc… If we value authentic human creativity and youthful energy, I’m not sure if AI will be a good substitute for the lack of young people in society.

In most periods of human history, young people have been at the forefront of culture, innovation and social change. Most subcultures have started as youth subcultures. Most of the revolutions have been started by people in their 20s or 30s. When there are protests against authoritarian regimes, most of the protesters on the streets are relatively young. Without enough young people, societies could become more stagnant and less dynamic.

Second, population decline could be a sort of vicious cycle: low fertility leads to less young (and fertile) people in society, less young people means less potential parents, and those few who remain are likely too be overworked and less inclined to have their own kids.

Third, if inclination towards having kids isn’t determined by genetics to a large extent, and if other factors can be strong enough to demotivate even those who do want to have kids from actually having them, then my optimism regarding our safety from extinction due to population decline (due to evolution solving it) is perhaps less warranted.

One reason for concern is the fact that many countries have spent over 50 years with sub-replacement fertility, without any signs of reversal. Of course 50 years might be nothing for evolution. It takes much longer for evolutionary effects to take place. But, this, in fact, could make the problem worse. We could face hundreds or thousands of years with sub-replacement fertility before the evolutionary effects kick in.

And population decline, just like population increase, is exponential. If a country lost 50% of its population each century (which is very likely under current trends), then China, for example, could have just around 1,400,000 (yes, one million and four hundred thousand) people in 3024.

And if the world starts losing the population (50% per century) starting from 10 billion in 2100, by the year 3000, the world population could drop to around 19,500,000 (nineteen million, five hundred thousand).

Now if it gets that bad, this could indeed endanger the survival of humanity. First, because we don’t know when it ends, second, because smaller populations are more vulnerable to genetic disorders, pandemics, natural disasters, etc. If some disaster strikes that wipes 99% of humanity, so that just 1% remains… the situation is very different if the original population was 10 billion ( which leaves 100 million survivors), vs. 19,500,000 (which leaves just 195,000 survivors).

Regardless of its effects on population, sub-replacement fertility is a SYMPTOM of a dysfunctional, perhaps even dystopian society

We might be living in a dystopian, dysfunctional society, even without noticing it. We don’t notice it, because that’s the only type of society we have ever lived in. We don’t know any better. Some people like Steven Pinker, even think that there has never been a better time to be alive than right now. Maybe he’s even right. But even if he is, it doesn’t mean that our current society isn’t dystopian in some important ways. Maslow’s pyramid of needs speaks for itself. We routinly fail to satisfy some of our most basic needs.

Sub-replacement fertility could thus be seen, not just as a warning about the impending population decline, but also as a symptom that reveals all the things that are wrong with our society. I hope this could serve as a starting point for a debate about the nature of our current social and economic order and whether this type of society is sustainable at all in the long term. If you remember, DeepSeek ominously suggests this might not be the case (“Sub-replacement fertility seems to be a persistent feature of advanced development.”)

I’ve suggested some potential ways it could be improved, but this is just a beggining, of what I hope will be a broader debate about state and sustainability of our societies around the world.

Another important take-home message of this post is that we should recognize certain dysfunctions of our society as types of poverty. Recognizing that we’re dealing with widespead poverty might also mobilize those who care about reducing poverty in the world, such as effective altruists. If fighting poverty is a noble and worthy goal, then perhaps all types of poverty should be included in this fight - including those which I discussed in this post.

I Thoroughly agree with most of the things you've written andI like the way in which you present things (in simple, reasonable, logical terms). My main observation here is that the people from the past didn't have it much better than today, but they did have kids, a lot more than us, simply because they didn't have widespread access to methods of contraception (including abortion).

I am sure if they had, the fertility issues we face today would have shown up a lot sooner in humankind history, with strong impact over the development of our race.

What I think is sad and also should be addressed is how much infertility affects a couple's live (1 in 5 couples are unable or have difficulty conceiving today). I think some measures should be taken in that direction, for example free treatment of such conditions for those people that really want to become parents. Lowering the age of starting a family should improve things a lot, as you proposed. Part-time jobs would help as well.

And also, I think the media and the loss of strong intimate relationships (friendships, community) has a big impact. I don't know the cause of this loneliness epidemic. I don't know ehat might be the solution to it..